Pearl Fishing: Fishin’ for the Crown

Pearl Fishing: Fishin’ for the Crown

Throughout Scotland live a people called the Nawken, traditionally a nomadic people organised into very close-knit family groups. They’re known to have lived in Scotland since at least the 12th century, their own oral history describing them as an Indigenous people to the land.

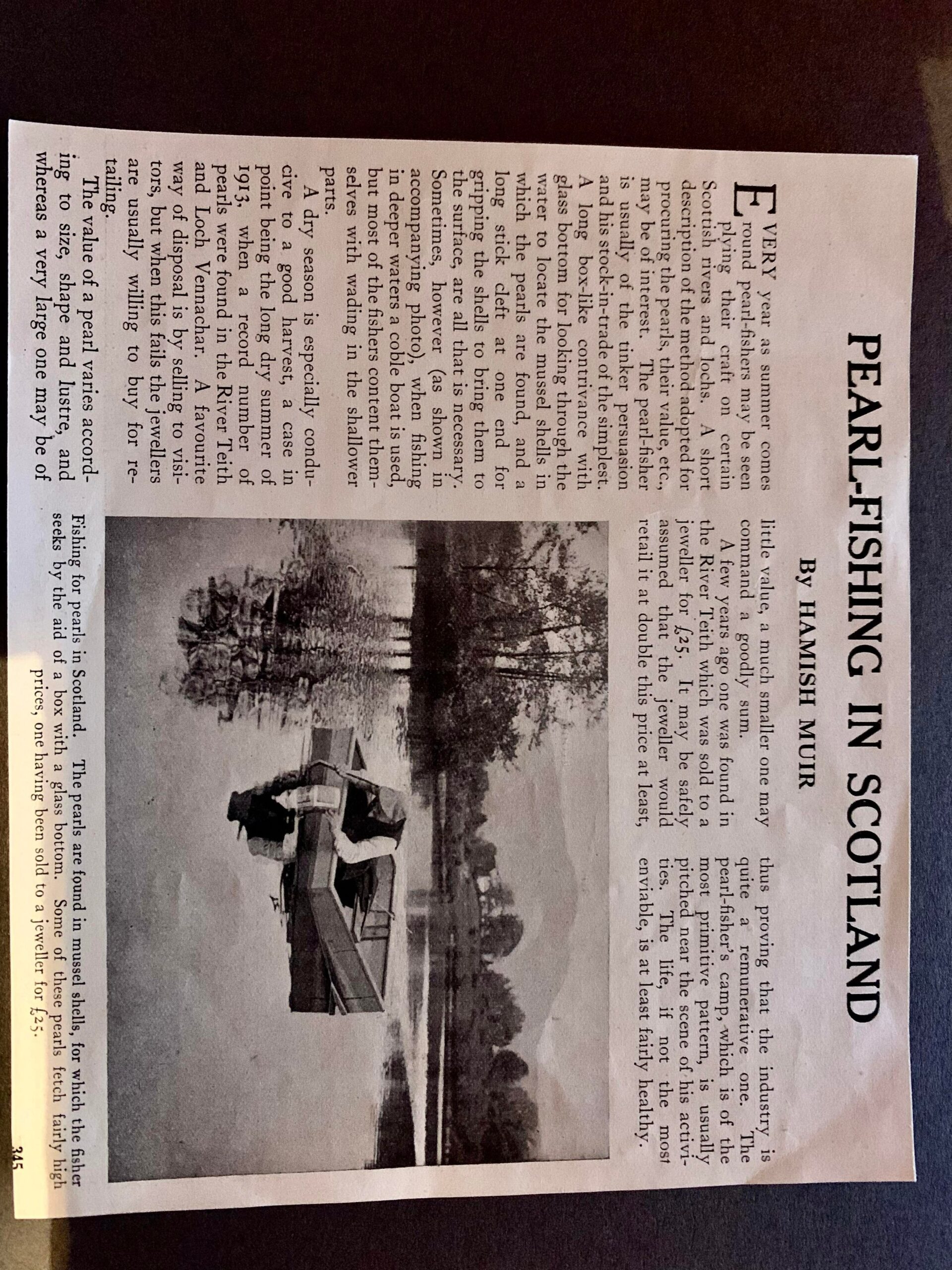

Nawken have deep knowledge of Scotland’s landscapes and importantly the foods that can be found there. However, there were some foods and provisions that can’t be garnered from the landscape, in these cases the Nawken relied on native species for trade. One clear example of this can be seen with freshwater pearls and the ancient skills required to fish for them.

One Nawken tradition bearer explained; “We’re as auld as the pearl, I mind when I was a wee boy hearing an auld auld Nawken coul [Nawken man] telling the story of the Romans bringing us to Scotland, we were their fishers you see – they needed us to get the pearls.”

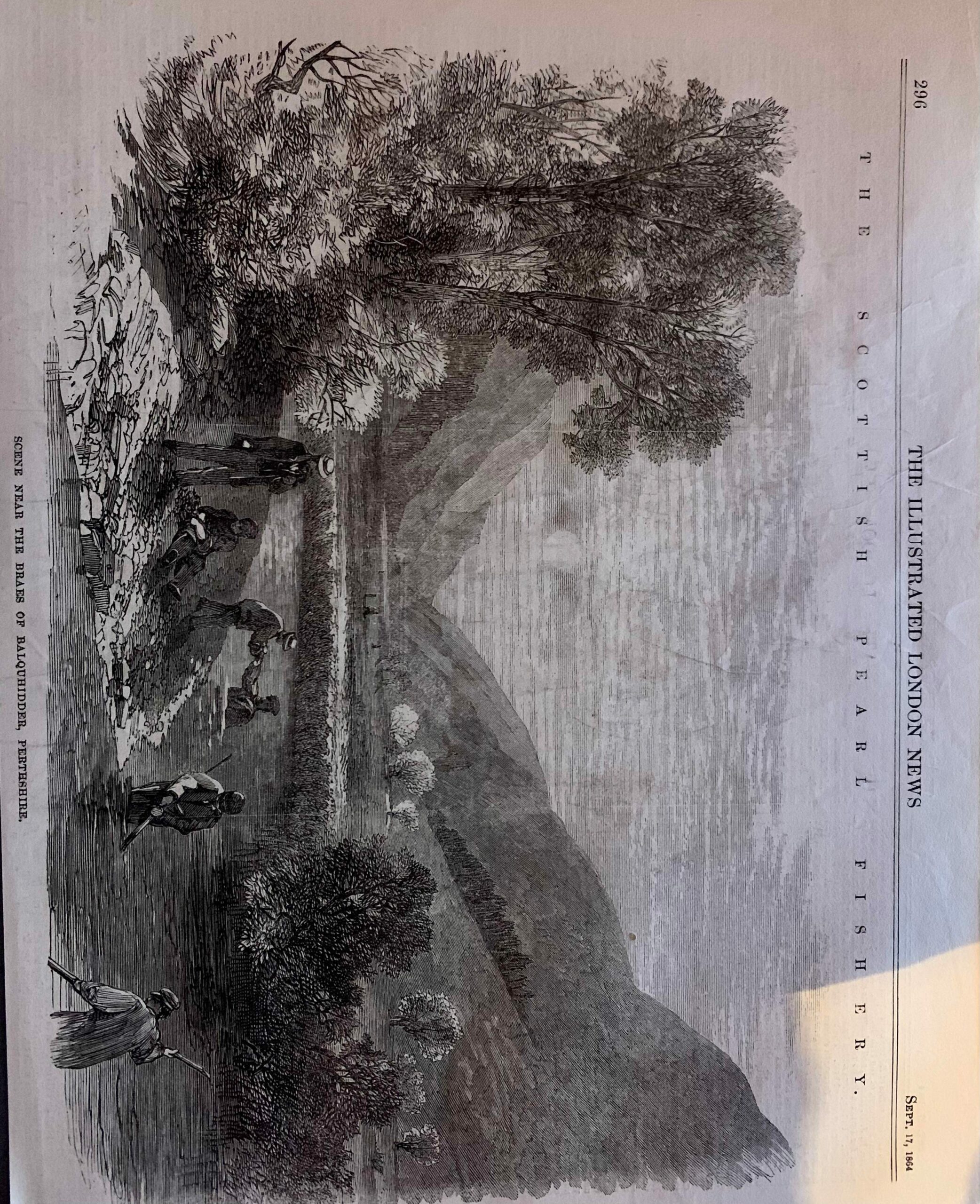

Many Nawken elders also use the expression ‘I’m away fishing for the crown’, which some have claimed relates to the pearls on the Honours of Scotland which may have been fished by Nawken centuries ago. Discussing the art of pearl fishing Nawken elders explained that freshwater pearls couldn’t be found in every river in Scotland, but that the best rivers were the Tay, Spey, Dochart, Don and Dee.

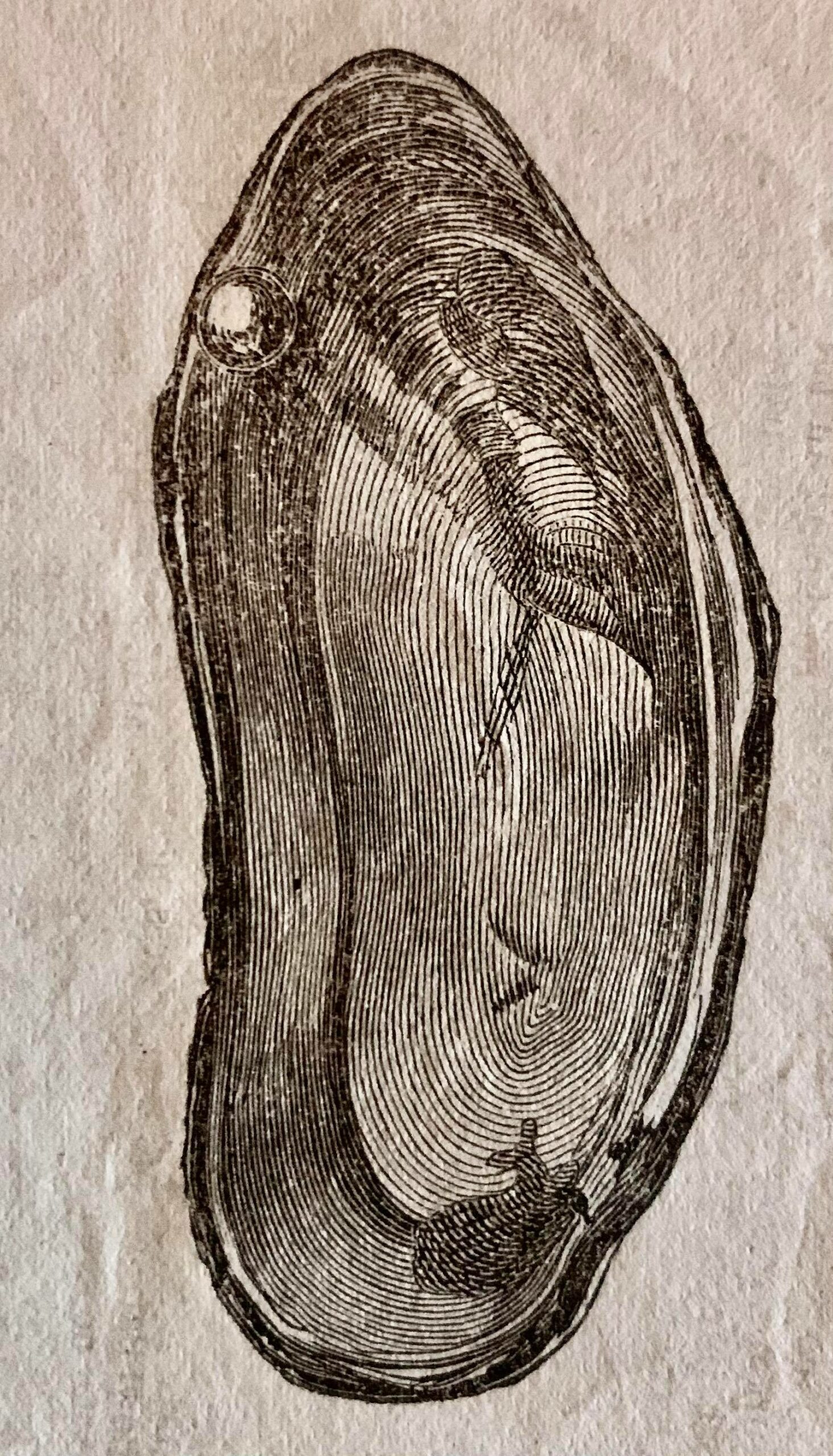

Fishing for pearls required patience, knowledge of the riverbed and an ability to ‘read’ the shell of a freshwater pearl mussel. Nawken have different words to describe the shell, including ‘clay shell’, a ‘crook’ and a ‘run’ – each differentiating the behaviour and sub-species of pearl mussel. This knowledge was crucial, as knowing that a particular mark on the side of the shell set it apart as a ‘clay shell’ or reading a ‘run’ on the shell and knowing the mussel has ‘spat out’ it’s pearl – meant knowing you would get no pearl in this shell and therefore you would avoid killing a mussel unnecessarily. Nawken were also taught to tell the age of a shell based on its markings, this meant that their practice of pearl-fishing could avoid damaging young mussel populations.

The art of pearl-fishing was taught to Nawken from a young age and a respect for the pearl mussel was crucial. One Nawken contributor explained that when he joined the army, he found map reading to be easy, as “reading the landscape was like reading the back of a shell, the re-entrants on the map were the crooks I’d been taught to look for as a child.”

One Elder explained that the mussel ‘knew when you were near them’ and that you had to read the riverbed gently in order for the mussel to present itself to you. Additionally. The pearls themselves were treated with deep veneration by the Nawken, with Elders claiming a pearl could ‘feel the personality of the person wearing it’ and that it’s colour would dull if worn by someone that you were not close to. Some families also claimed that whilst valuable to sell, a black coloured pearl was an unlucky pearl for Nawken.

Most pearls fished by Nawken were sold to Jewellers, one famous example was Cairncross jewellers in Perth. However, some were also kept – ‘flat-backs’ that weren’t valuable to jewellers were made into jewellery for Nawken themselves – and others traded for food, clothes, and provisions.

Whilst the fishing of freshwater pearls in Scotland was made illegal in 1998, many Nawken still talk fondly of their experiences pearl fishing and there are still deeply emotive arguments made around the criminalisation of the practice.

Nawken claim that the decline in the mussel population was not the result of their practice – that they state had existed in balance with mussels for centuries – Instead, the decline was the result of three key factors;

1) overfishing by non-Nawken people who lacked the ancestral knowledge to read the mussel shell and differentiate, leading to them taking and killing ‘everything including the young shell population’

2) Increased flooding, changes to the river environment and landscape

3) Changes in agricultural farming, specifically the increased use of fertilisers, alongside waste and pesticides being dumped into river courses.

Whatever the reason for the decline in mussel population, Nawken claim that they weren’t consulted on the change in law and feel an alternative route could’ve been posed. For example, one Elder stated how a licence based on hereditary rights should’ve been granted to Nawken ensuring the traditions and cultural importance of pearl-fishing would not be lost.

Nawken elders seem to express a profound belief in the resilience of nature, one elder joking that ‘they’ll move to a fresher bit, ai!’ when discussing water pollution impact on mussel populations. It seems the Nawken reflect nature in their resilience and adaptability to change.

Pictures

Reading Links

Whyte, B. (1975) PEARL FISHING AND SELLING PEARLS. Tobar an Dualchais [Available from: https://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/track/110259?l=en]

Robertson, S. (1981) The equipment used for pearl-fishing; two record pearls found in the River Don. Tobar an Dualchais [Available from: https://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/track/42844?l=en]

Stewart, A., Stewart, B. [1978] Anecdotes about pearl fishing in Ireland and Scotland, and selling pearls. Tobar an Dualchais [Available from: https://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/track/57342?l=en]

Acknowledgements

Sincere thank you to the Nawken people, specifically Mr Dave Donaldson and Mr Jimmy Williamson, Nawken elders, for sharing their knowledge and memories of pearl-fishing.